![David Gower [Image: Mark Leech/Offside via Getty Images]](/images/media/David-Gower.jpg)

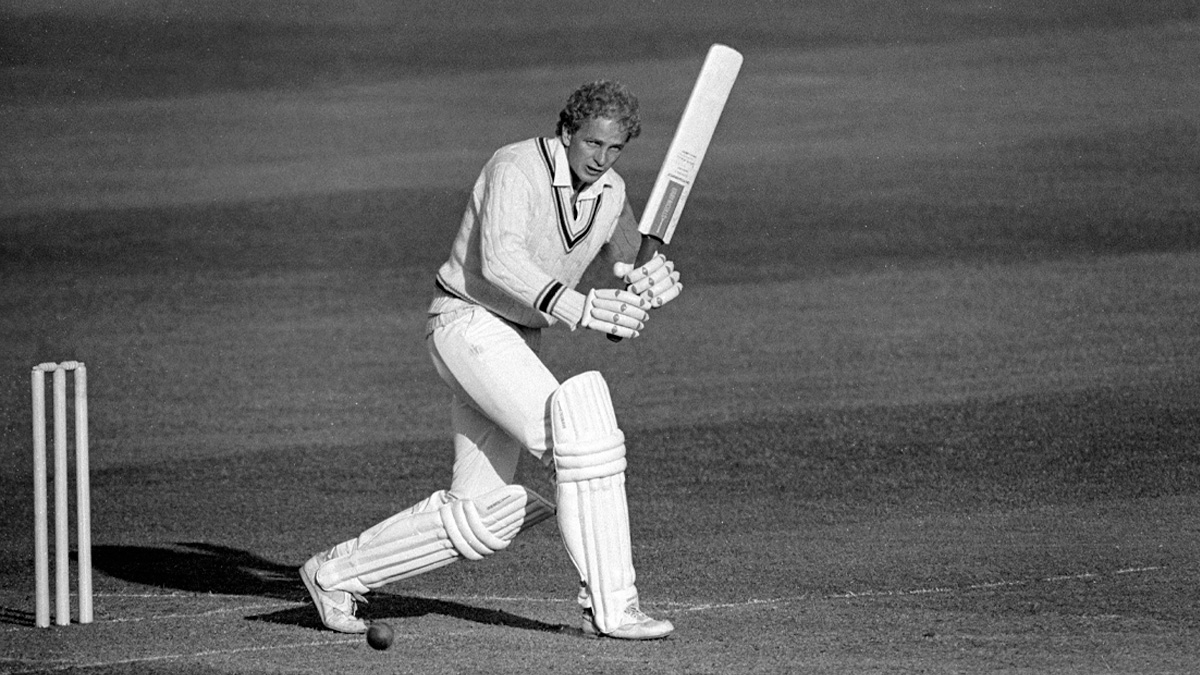

Imagine a 12-year-old boy staying up past midnight by the embers of a log fire, tuned to the radio, waiting for the start of a Test match in Australia. When play finally starts, I listen to David Gower, prince of style, make a rapid-fire yet languid hundred. “Effortless” is, as usual, the word the commentators reach for.

I saw Gower recently and brought up the innings. Had he decided to do anything differently that day? No, he said, it simply clicked and everything was in sync. As expected, I suppose. But he did add one surprise: underneath it all, he was angry.

You’d never have guessed it from the smooth flow of his back-foot drives. That contrast – surface calm, deeper emotion – is worth returning to.

Writing about your own moments of form and clear focus is vulnerable to retrofitting, especially if you’re interested in ideas. Is the “zone” you describe really your own or an amalgam of lived experience and borrowed theory?

Of course, a writer is doubly vulnerable here. “Here’s how I was in the zone” can blur all too neatly into “Here’s how I am in the zone.”

So I will try to be especially cold-eyed and un-intellectual in trying to make sense of three spells in my cricket career when batting came to me freely and easily. They were all different.

Aged 19, I averaged a hundred or so in first-class cricket for a chunk of time, enough to put me at the top of the national averages, which were published in the broadsheets and carried a weight (both the first-class averages and broadsheets) hard to imagine today.

But I was spending most of my time studying for exams at university. I would cycle to the ground with my kit on my back, another good day at cricket would follow the last, and then back to my studies.

I was innocent, really, and my confidence was sky-high but untested. The “formula” I’d stumbled on wasn’t really about batting but about life. I had momentarily achieved balance, concentrating equally well in two contrasting areas of life – history and cricket – each reinforcing the other by making space for it.

I quickly lost that balance and, in truth, probably never quite regained it in my playing days. And it was the trauma of losing balance (rather than achieving it) that gave me an insight I’ve stayed close to in subsequent careers: focus can be best achieved obliquely, almost by accident. We have to fall into step with our creativity, which is an art rather than an army drill.

It was a long six-year wait – and much time to curse feeling average – until July 2003, and this sequence of scores that led to my England selection: 135, 0, 122, 149, 113, 203, 36, 108. (Entirely characteristic, by the way, for me to squeeze a nought in there, even in the form of my life.) The scores alone don’t quite capture how quickly the hundreds came. When I made 203, I was scoring fast enough to get 300 inside a day.

Effectively, I’d abandoned being a defensive player. And I was angry – angry I’d been led down that path in the first place. So even though those innings mostly “played themselves” and all I had to do was get out of my own way and watch the ball, underneath it all was a sense of making up for lost time. In place of innocence, here was defiance: six years lost, six centuries made. You don’t get 19 to 25 back and I was in a hurry.

True to form, once I found what I was looking for, I over-complicated it with distractions: publishing a book, arguments, introspection. The next season was the hardest. Playing carefree was out of sight. You can lose your balance by being too narrow and bored; and you can lose it by being stretched and spread too thin.

I missed at both ends of the spectrum at different times. But by the end of the season, I was tired of thinking and finally let go again. I started to concentrate and then came another run: 70, 156, 106, 189. That was probably the best technical form I ever achieved. The good form felt less fragile. It wasn’t intoxicating or exhilarating, it was free and controlled. Grown up, perhaps?

The child in me almost retired on the spot. And the child was right. There were four more seasons, but nothing better. As usual, I was looking at all this through a writer’s lens as well as a cricketer’s. I got drawn into Bob Dylan’s book Chronicles, which opens with his early adulthood in Greenwich Village, where I lived during the cricket off-season.

I reviewed Chronicles in The Spectator that winter, and my preoccupation with form obviously conditioned my reading. Finding and Losing a Voice, the headline writer titled it. Finding and Losing and Finding a Voice would have been another take. That’s how I came to see sport and writing. Cricket had given me a crash course.

There’s a wider and more social framing now. Growing up in the 80s and 90s, concentrating was a lot easier. No internet, no smartphones, no social media. Today, concentration is the front line in a war for attention – and we’re losing. Which creates another paradox. I used to think of sport and the arts in opposition, vying for my attention.

Now they feel unified and aligned. In the age of commercialised distraction, any sustained focus is an achievement, even a refuge. My generation grew up lucky.

Related and recommended

Spells of rare sporting brilliance show that finding intense concentration relies on achieving balance in your life

Rohan Blacker looks back at his time with e-commerce pioneer Sofa.com and explains the thinking behind his latest online furniture project

Rory Sutherland is one of the UK’s best-known marketing thinkers. He sets out why businesses should rethink how they value marketing, from direct mail to call centres and customer kindness

Leaders must realise the tech revolution can achieve its full potential only when human values remain central to change