Some of the most recognisable names in business have learned the hard way that past dominance is no guarantee of future success. HMV, Nokia and Kodak each built global reputations by shaping – and in some cases defining – their industries.

HMV’s high street record stores were once the beating heart of the UK’s music scene, Nokia’s mobile phones were a fixture in millions of pockets and Kodak’s film captured generations of memories. For decades, they were market leaders with loyal customers and enviable brand power.

Yet all three fell victim to the same underlying challenge: failing to adapt quickly enough to disruptive change. For HMV, it was the shift from physical music sales to streaming; for Nokia, the rise of smartphones and the software ecosystems that powered them; for Kodak, the transition from film to digital photography and online image sharing.

In each case, competitors seized opportunities that the incumbents either underestimated or misunderstood. While all three brands survive in some form today, their influence has faded. Their stories are stark reminders that innovation is not a one-time achievement but a continuous process – and that in fast-moving markets, yesterday’s winning formula can quickly become today’s cautionary tale.

HMV: High-street hero left playing the wrong tune

The year is 1921 and at 363 Oxford Street in London a new shop is opening. Named His Master’s Voice, it was the beginning of a retail brand that would come to define the music scene of the 1970s, 80s and 90s and the industry’s – and its own – decline in the early 21st century.

The business that would become HMV was set up in 1898 by Emile Berliner, who invented the gramophone, to make and sell records to independent shops. It was called the Gramophone Company, but Berliner and his co-founders knew they needed something to make their products stand out. They found that in His Master’s Voice.

The name comes from a painting by Francis Barraud of his dog Nipper listening to a cylinder phonograph designed by Edison. The Gramophone Company bought the painting and the trademark rights to it in 1899 and – with a small tweak to replace the phonograph with a gramophone – began using it on its products.

It wasn’t until 1921, however, that His Master’s Voice became a brand with the opening of that first shop. It operated that one store for 45 years before, in 1966, it began opening new stores in London. It expanded through the 1970s, becoming the UK’s biggest specialist music retailer, and opened what it claimed was the world’s largest record shop at 150-154 Oxford Street in 1986.

Growth continued through the 1990s, with its popularity boosted in part by live music. Performers such as Sir Paul McCartney, Michael Jackson, INXS’s Michael Hutchence, Madonna and Sister Sledge made appearances at its stores, knowing that it could make a decisive difference in sales of their latest releases.

During the 2000s, HMV bought rivals such as Fopp and Zavvi and entered the live music business. However, sales of physical retail were starting to fall as digital music took off. HMV launched its own social network and bought a stake in 7digital. It wasn’t enough. In 2012, revenues from digital music overtook those from physical music and just a year later, HMV appointed Deloitte as administrators.

It was bought out of administration by the restructuring firm Hilco but had to close more than 100 shops and make large-scale redundancies. And while in 2015 it was the biggest physical music retailer, that market was in freefall as digital music expanded.

By 2018, it was facing the prospect of going into administration again, only to be rescued by the Canadian record shop chain Sunrise Records. HMV is still operating today, but it has only 121 shops and its influence on the music industry is much diminished. The resurgence of vinyl has helped to shore up sales, which reached £190m in the year ending May 30, 2024, and it is still profitable, generating £3.9m in the same period.

But compare that to Spotify, which in 2024 generated €15.7bn, or the UK music industry overall, where retail sales reached £2.4bn, and it’s clear HMV was disrupted by the rise of digital, failed to innovate and was overtaken by disruptors who came in and stole its market. It saw too late the threat that music downloads and streaming posed and could not turn its high street success into online dominance.

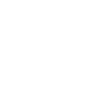

Nokia: mobile pioneer made the wrong calls

Imagine holding almost a 50 per cent share of a global market, only for that to drop to just 3 per cent six years later. That’s what happened to Nokia.

The Finnish company arguably kick-started the growth of the mobile phone industry. It was by no means the first to market, but it brought the mobile phone to the masses. It was also first to launch an internet-enabled phone in the mid-1990s and pioneered the touchscreen mobile device in the early 2000s.

One of its most iconic devices – the Nokia 3310 – sold more than 126 million units worldwide after it was released in 2000. It had several features rare at the time including a calculator, stopwatch and reminder function. It also, of course, came with Snake II, the hugely popular follow-up to the original game.

By 2007, its market share was 37.8 per cent, according to research analysts Gartner. It was by some stretch the biggest mobile phone seller in the world, ahead of Motorola on 14.3 per cent and Samsung on 13.4 per cent. Apple was nowhere to be found.

That would soon change. At a convention centre in downtown San Francisco in January 2007, Steve Jobs walked on stage and revealed the iPhone. The result of three years of work, it turned the mobile phone market on its head when it went on sale in June that year.

What Apple understood – and Nokia did not – was the importance of software. Nokia had put all its efforts into producing the hardware, creating great devices, but could not compete on the software.

Nokia’s fall was swift. By 2010, its market share was down to 28.9 per cent; by 2014, it was 9.9 per cent. Its performance in the smartphone market was even worse. Having held 49.4 per cent of the market in 2007, it was down to 3 per cent in early 2013.

Nokia eventually sold its mobile phone business to Microsoft. During the announcement of the acquisition, then chief executive Stephen Elop concluded his speech by saying: “We didn’t do anything wrong, but somehow we lost.”

That, perhaps, summarises what went wrong at Nokia. Management knew it had a strong position, but it had failed to adapt to a changing landscape and the rise of deep-pocketed competitors. It could not shift its focus away from hardware to software and ecosystems – and it got left behind.

The company still exists as a very successful – if slightly dull – network equipment business. Revenues last year were $20.8bn (£15bn). Phones are also still sold under the Nokia brand: Finnish phone maker HMD Global bought the rights in 2016.

But Nokia itself was innovated out of the market. Apple came in and changed the game and where others, such as Samsung and LG, were able to react, Nokia could not. Once its slide started, it became impossible to arrest.

Kodak: Photo giant could not see the bigger pic

Capturing a “Kodak moment” used to be about preserving a moment in time. Now, it’s more likely to be about avoiding what befell a market leader.

In 2012, the company filed for bankruptcy. It was a sharp fall for a business that basically invented the idea of amateur photography. At one point, Kodak controlled almost 70 per cent of the US film market, had gross margins of close to 70 per cent and one of the strongest brands in the world. Then along came digital.

The common misconception about Kodak is that it failed to invest in digital and got left behind. But that isn’t quite true. In 1972, it set up a team to work on digital technologies. That team invented features now ubiquitous in everything from smartphones to medical cameras to drones.

The first prototype of a digital camera was created in 1975 by Steven Sasson, who worked at Kodak. That camera bears little more than a passing resemblance to cameras now: it took 20 seconds to load an image, required complicated connections and was huge: “the size of a toaster,” according to Sasson himself.

Despite all this, it clearly had the potential to revolutionise the camera industry. But Kodak was not convinced. “The reaction I got from Kodak management was one of curiosity and scepticism, as it did not feel like a major invention,” Sasson told digital photography website PetaPixel.

“There was not a real feeling that we had invented something. Indeed, they didn’t ask me how this worked. They simply asked me why anybody would want to take a picture this way when there was nothing wrong with conventional photography.”

Nevertheless, Kodak did invest in digital. It spent billions developing a range of digital cameras. But it overshot. Rather than focusing on how digital could make taking a picture simpler, it tried to replicate the performance of film in digital – something that wasn’t possible at the time.

It also failed to spot the shift in how people would use photos. It bought the photo-sharing site Ofoto in 2001 but used it to try to convince people to print pictures. In the end it sold Ofoto to Shutterfly for just $25m in its bankruptcy plan. That month, Facebook bought Instagram for $1bn.

The lesson from Kodak is not so much one of ignoring an innovation in the market as not being able to spot the real ways it would disrupt the industry. The shift to digital was less about expanding the printing business and more the transition to sharing pictures online. For Kodak, photography was still about preserving moments. For everyone else, it was about sharing experiences.

While Kodak no longer defines how the world captures its memories, the company itself has not vanished. Instead, it has quietly reinvented itself, shifting focus from consumer photography to commercial printing, advanced materials and speciality chemicals.

The yellow Kodak logo may no longer dominate family photo albums or camera stores, but its legacy endures in boardrooms and business schools as a warning of what happens when you fail to grasp where innovation is going.

Related and recommended

Spells of rare sporting brilliance show that finding intense concentration relies on achieving balance in your life

Rohan Blacker looks back at his time with e-commerce pioneer Sofa.com and explains the thinking behind his latest online furniture project

Rory Sutherland is one of the UK’s best-known marketing thinkers. He sets out why businesses should rethink how they value marketing, from direct mail to call centres and customer kindness

Leaders must realise the tech revolution can achieve its full potential only when human values remain central to change